The views expressed herein are those of the writer and do not represent the opinions or editorial position of I-Witness News. Opinion pieces can be submitted to [email protected].

Part 1 – Innovation, or strategic blunder?

When bearing good news politicians are, perhaps understandably, prone to a bit of exaggeration. With elections around the proverbial corner, noses get even longer. And then there are tales of complete fantasy, such as the announcement by Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, made at the official launch of the St Vincent geothermal project in July 2015, that St Vincent and the Grenadines is on track to have 10 to 15 MegaWatts (MW) of geothermal capacity installed and delivering geothermal energy to the country by the end of 2018.

The geothermal project launch, spanning the better part of a week, was designed for maximum public relations benefit and clearly intended to inspire confidence; to demonstrate that this government is on top of things in relation to the implementation of renewable energy in St. Vincent. The facts, however, tell the opposite story. This government, which took office at the turn of the 21st century, has comprehensively mismanaged the energy sector as far as the sustainable energy future of the country is concerned — and especially so in relation to geothermal energy.

The Prime Minister’s proposed schedule for having geothermal energy online is not even optimistic — it’s wildly fanciful and completely unrealistic. But we’ll get to the schedule later. Let’s look first at the big, strategic picture, starting from the point where Dr. Gonsalves had his golden opportunity to make a mark on the energy future of this country.

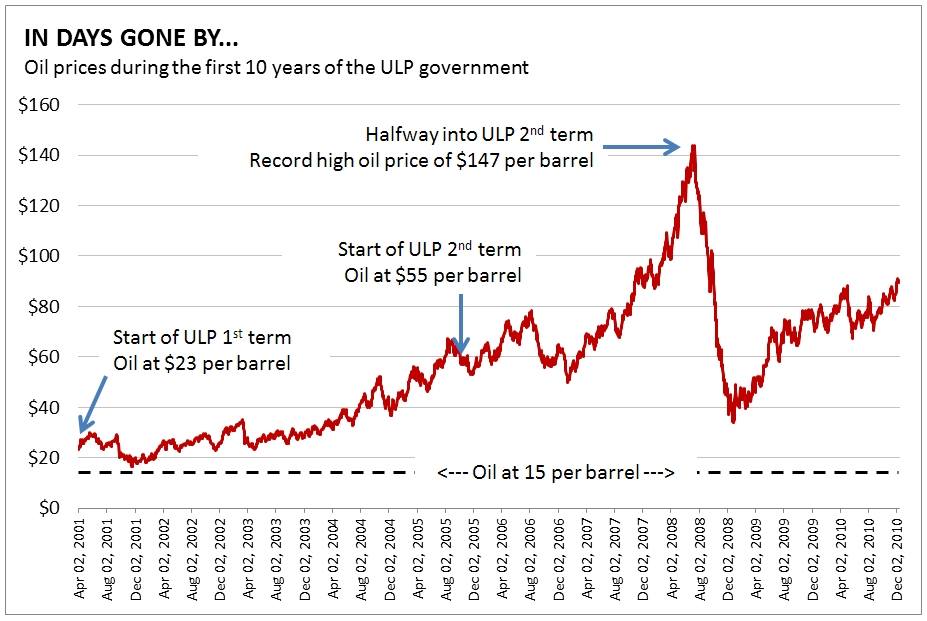

A useful point of entry to the strategic discussion is provided by Dr. Gonsalves himself when, speaking to the press in January 2015 about his government’s geothermal development plans, he correctly noted that “in days gone by, when diesel was 15 dollars or less per barrel, there was no real urgency to address the other forms of energy”.

It’s a critical point in relation to the economics of energy. There is indeed some notional, not-quite-specific price of oil which can be considered a benchmark of urgency. Below that price, oil is cheaper than the alternatives and therefore not worth worrying about (in financial terms anyway); above that price, alternatives become cheaper and more attractive. But valid though the point may be, it’s problematic for the person making it. The problem is that the price of oil was never at US$15 or less per barrel at any time during his tenure. (Presumably the prime minister was referring to the price of crude oil, which in any case costs less on a volume basis than diesel). The last time we saw crude oil prices at $15 levels was in June 1999 — almost two years before the ULP took office.

Oil prices were flat at around $20 a barrel (more or less) for the 14 years that brought the 20th century to a close. But by 2001, oil prices were already on an upward path and were at $23 a barrel when Dr. Gonsalves took his oath of office on April 1. By the time his first term was drawing to its end, oil prices had almost tripled, reaching $65 a barrel — more than four times the benchmark of urgency he has recently proposed — and things only got worse from there. The situation becomes clear when you peruse the figure below, which shows the price of crude oil during the period April 2001 to December 2010 — the first two terms of Dr. Gonsalves’ government.

In fact, during 2001 to 2008, the global oil market experienced an unprecedented increase in prices. At no time in the history of the modern global oil market (dating back to the formation of OPEC 55 years ago) had there been such a massive increase in oil prices — constituting a crisis that was part and parcel of the 2007/08 global economic meltdown. At its climax, oil prices peaked at close to $150 per barrel in July 2008 — which is 10 times as high as Dr. Gonsalves’ proposed benchmark.

The question, therefore, has to be asked: given these recent comments, what did Dr. Gonsalves (who is also minister responsible for energy) do back then, in response to a situation that had decisively gone past the state of being urgent during his first term in office? To put the question more specifically in relation to the core problem: what did this government do to address the problem of our country’s increasing dependence on expensive, imported fossil fuels, when there was a clear need for focused, decisive action in favour of renewables?

As it turns out, not much.

Leaving aside the present developments for the time being, two major milestones in the energy sector were achieved during the fourteen year tenure of this government. The first was the design and implementation, during 2003-07, of a new, flagship diesel powerstation at Lowmans Bay, which became the base-load power plant in the country, replacing the Cane Hall powerstation (which was approaching the end of its useful life). This development was an example of the normal process of renewal that has been undertaken — and achieved — over the history of our electricity sector. The second milestone was that the government signed the country on to Venezuela’s Petrocaribe initiative — an action which, whatever its other benefits, has had the effect of increasing our country’s dependence on fossil fuels (not to mention our national debt). Neither of these developments has advanced the cause of renewables in any fashion.

Specifically in relation to renewables, there were some things done which should, on their faces, count as significant. A national energy unit was set up in 2008 — but this was almost an afterthought for the record, taking place when the crisis had already reached its zenith. The government published a national energy policy in 2009, followed by an energy action plan in January 2010. The energy action plan incorporated a list of 35 short-term actions considered necessary to put the energy sector on a sustainable path. Today, more than five years later (ie: past the short-term horizon), only about 11 of the 35 short-term actions have been undertaken. That’s a very low achievement rate of just 31 per cent, which would constitute an ‘F’ grade in most contexts. In recent years the state-owned utility has implemented needed upgrades to its hydro facilities, and has also embarked on an economically and strategically flawed foray into solar photovoltaics.

Oh, and the prime minister signed, in May 2008, a memorandum of understanding with “CGE Ltd, a company duly incorporated under the laws of St. Vincent and the Grenadines and represented… by Robert Croghan, President and Chief Executive Officer” for the exploration and development of the country’s geothermal resources. Which would seem to be a good thing, until you consider the strange fact that if you were to Google CGE Ltd, Croghan Energy or Robert Croghan, you would find nothing to suggest that he or his company had any knowledge, specific expertise or track record in developing geothermal energy projects. Nothing. And yet, the prime minister of this country signed a one-year MOU with this entity to develop the geothermal resources of this country. Predictably, nothing happened during the year and inexplicably, the MOU was allegedly extended for at least one other year, following which everything went silent.

It should go without saying that if any of the prime minister’s advisors had spent an hour or two looking into the bona fides of this so-called “developer”, he would have been advised to steer clear of a geothermal developer with no track record in developing anything related to geothermal. Be that as it may, the reality is that during the period 2008 to 2012, the geothermal development milestones achieved by this government amounted to, practically speaking, nothing.

While this general ineptitude was playing out in Kingstown, the government of Dominica, our neighbour to the north, was going about its own business in a coherent, informed and focused fashion. During the period 2005 – 2014 Dominica’s government:

- accessed OAS grant funding and technical assistance to start preliminary geothermal explorations;

- set up a specific geothermal project management unit within its energy unit;

- applied for and received EU-funded grants for full-scale geothermal exploration (drilling);

- contracted with credible and experienced geothermal project developers to perform the drilling and analysis of wells;

- drilled three exploratory wells, one production well and one reinjection well and confirmed that Dominica indeed has a geothermal resource estimated at about five times the size of its peak electricity demand.

Note that this impressive list of achievements took Dominica almost ten years to accomplish. Also note that all of the above was paid for by grants and public funds; a fact of fundamental significance, which we will explore in detail a bit later. Now, at this point, Dominica has completed its drilling programme and is moving to the stage of design and construction of a geothermal power station.

Which brings us back to the situation in SVG, and an examination of what’s happening now. Which, in a nutshell, is that having mostly wasted the past decade, this government is now taking precisely the wrong approach in the development of a geothermal project for this country.

An article recently published by Ellsworth Dacon, SVG’s director of energy outlining St Vincent’s geothermal development approach actually sheds some official light on the matter. Early on, the author informs the reader that “an innovative approach” is being taken by the government — a red flag to knowledgeable readers, if previous “innovations” in this government’s approach to infrastructure development projects are any indication.

The so-called innovation appears to hinge around a memorandum of understanding that was signed, in January 2013, with a private consortium comprised of Reykjavik Geothermal of Iceland and Light & Power Holdings of Barbados (a subsidiary of Emera Inc, a Canadian company). Interestingly, we are also advised in this regard that “the government felt it was very important to seek out partner companies with substantial technical, development and operating experience and with credible financial capacity to develop the project”, a requirement so glaringly obvious that it should almost go without saying. Isn’t that what any government is supposed to do? But the statement is inadvertently telling, since back in 2008 the government clearly was under no such compulsion when the prime minister signed the country up with a partner company having none of the above.

Then the article advises that “a dilemma” was faced by the consortium and the government in signing their MOU. The dilemma appears to be based on the fact that geothermal development is expensive and involves high levels of risk in the early, exploratory stages. In short, there is no guarantee that a viable geothermal resource is located at location X until an actual geothermal well is drilled at location X — and drilling geothermal wells is expensive: those drilled in Dominica went down to depths of up to 6,000 feet and cost in the region of US$4 million apiece.

So it means that someone has to spend a significant amount of money up front, with no guarantee of a positive outcome. And even if the geothermal resource would eventually be proven, the cost of the resulting electricity is still unpredictable until after the fact. As the author explains it, “without completing the expensive upfront scientific work, the actual cost of power from the project was highly uncertain.”

The consortium therefore “required some assurance that, if it invested in doing this scientific work and the results were favourable, it would be able to earn a sufficient rate of return to justify the investment. On the other hand the government’s objective was keeping the cost to supply power from the project as low as possible”, which constituted the purported dilemma.

The agreed solution was that the private sector consortium would “fund the upfront work which will result in a detailed business plan establishing the promise of the geothermal resource, the costs to develop it, and an action plan for development.” In addition, the article advises, “In exchange for making this investment, the consortium gets the exclusive right to negotiate with the government to develop the project under an Independent Power Producer (IPP) framework.”

Essentially, under this framework, the consortium and the government would form a company that would negotiate a power purchase agreement (PPA) with VINLEC, under which they would sell geothermal electricity to VINLEC, which VINLEC would distribute and sell to us consumers. In this regard we are advised (emphasis mine) that “the cost of power in the PPA will be based on the actual costs of the project and a pre-agreed rate of return for the project.”

So several things are clear at this point. One is that because the private consortium is financing the expensive upfront costs, it is now in a privileged position; acquiring exclusive rights, and so on. The second thing is that the money that the consortium will spend on the upfront work will be booked by them as a capital investment, on which they will receive a “pre-agreed” rate of return. Add the fact that the private consortium is taking on all of the financial risk in this defining, early stage of the development — which only makes their expectations for a rate of return even higher. All of these incurred costs and expected profits will have to be covered in the power purchase price. In other words, when electricity from geothermal starts flowing into the grid, the price us consumers will pay for it will include the upfront money the consortium is spending right now, plus their pre-agreed profit margin on that money as well as other costs yet to be incurred.

And it is at this point that knowledgeable observers would ask: why did this so-called dilemma arise in the first place? Again, Mr Dacon’s article sheds light on the matter (again I suspect inadvertently). He notes that the government’s “failure to attract grants to aid in developing its geothermal resource beyond the prefeasibility phase”, has led to its adoption of this approach. The real answer, however, is encapsulated in the word “failure”, for the problem exists only because the government of SVG completely dropped the ball years ago.

First of all, it’s not a matter of “attracting” grants. Grants don’t fall into a government’s lap, as if by some sort of financial gravity. A government must proactively put in the necessary work to develop and submit a coherent grant application, one that would be worthy of consideration. That’s what this government failed to do, between 2005 and 2010, when European Union grant funding windows were open to finance geothermal development projects in the Caribbean. During this period, Dominica’s government successfully applied for and negotiated not one, but a series of grants, for its own geothermal exploration programme. SVG’s achievement in that time was … to sign up with Robert Croghan. So yes, there is a problem, but it is a problem caused entirely by the negligence and ineptitude of this government.

For electricity consumers in SVG, the practical upshot of the above is simple. Guess who will be calling the shots during negotiations on the price of the electricity later on? On that note, the article advises that “the cost of power in the PPA will be based on the actual costs of the project and a pre-agreed rate of return for the project. If these costs and the pre-agreed rate of return do not result in a cost of power below current costs and favourable to consumers, the government is under no obligation to move forward with the project” — which amounts to nothing more than a mountain of nonsensical rhetoric. How likely is it that this government will walk away from the proposed project if that happens? That after its “innovative approach” has encouraged the private consortium to invest millions of dollars, on which they already have locked in a pre-agreed rate of return; everyone would simply walk away from the project if it resulted in numbers that are higher than current costs?

A more likely scenario is perhaps suggested by the prime minister’s reported remarks at a Brooklyn, NY town-hall meeting in September 2013, where Dr. Gonsalves, speaking about the geothermal programme, unveiled the exciting — and entirely speculative — prospect of St Vincent exporting geothermal-based electricity to Barbados. In what was perhaps a Freudian moment, the prime minister mused about the Barbados company’s supposed intentions: “Now, no one seriously believes that Emera will come to St Vincent to put in the facilities to generate only 10 MegaWatts of power” he said. “They have their eye on a larger prize” — which is a truly eyebrow-raising statement for the prime minister of an independent country to make on behalf of a group of private investors. By the same token, no one should now seriously believe that this very prime minister would walk away from a project where the very same investors, eyes on their “larger prize”, are expecting a “pre-agreed” return on their investment — even if that inconveniently requires consumers to pay an unfavourable price. When has such a thing ever deterred investors who find themselves in a monopoly position?

Conclusion

A final point is to be made on the so-called innovation in the government’s approach. A public-private partnership is a commonly-used mechanism for geothermal projects (and power projects in general) but is typically employed at the later stages of the geothermal development programme — where financial risks are low — rather than at the beginning. There are two good reasons why this should be so. First is that private investors typically seek to reduce, not increase, their investment risk. If, however, they do take on increased risk, it is always with the understanding that their expected rewards will be higher. Which explains the second reason: governments typically seek grants to finance the high-risk phases of their projects. So that if and when the geothermal resource is proven, the government (and by extension the people and the country as a whole) has a full and undiluted stake in the ownership of the business up to that point — and the final electricity cost is lower, as it does not have to include the profit margins on large sums of money invested up front by private investors.

To reiterate this point: the use of private capital at the early, highest-risk stages of the process is absolutely the wrong long-term approach for this country. In practical terms, it puts private developers firmly in the driver’s seat and allows them to have an undesirable level of financial interest and leverage in a resource which, properly developed, should belong in perpetuity to the country and its people. And, if this geothermal development plan goes ahead in its present form, the price we consumers will pay for the eventual electricity will be higher than it should have been had our government not bungled the business years ago. As it stands now, the government’s mismanagement of this hugely important matter is poised to impose yet another unnecessary burden on the citizens of this country. That all of this is now being passed off as an example of beneficial innovation and leadership (a word liberally tossed about at the project launch event) is only adding gross insult to the grave injury already perpetrated.

If the government’s approach were as innovative as they suggest, here’s what they should have done instead over the past 10 years:

- Apply for and secure grants to finance the geothermal development program, including the high-risk, upfront work (as Dominica did);

- Form a company by inviting the local and regional private sector to invest in shares alongside government/VINLEC;

- Hire the necessary technical expertise into the company to develop the geothermal project through exploration and up to the stage of construction;

- Procure, through a transparent bidding process, a suitable international firm to design and build the geothermal powerstation;

- If necessary at this point the government could sell a portion of its shares to this firm, but in any case the government would hire the firm to operate the powerstation for a specified period, after which time any shares purchased could be transferred to VINLEC and other local private sector investors;

- And last but not least: properly regulate the electricity sector so that the various companies would not be able to operate to the disadvantage of consumers in the future.

That’s what real innovation, which would have benefited the country as a whole, would have looked like. Instead, what we have is almost a worst-case scenario, where local involvement in this “game-changer” is likely to be at a bare minimum; where the majority of the benefits (ie: perpetual profits from the sale of geothermal energy) will accrue to the foreign investors and where the corresponding burden will fall, unsurprisingly, onto the citizens of this country.

We’ll talk about the project schedule, project costs and Petrocaribe in part 2.

Herbert A (Haz) Samuel

The opinions presented in this content belong to the author and may not necessarily reflect the perspectives or editorial stance of iWitness News. Opinion pieces can be submitted to [email protected].

Many thanks for this thoughtful analysis. My only reservation is that in the developed countries, projects like this tend to be entirely financed by the private sector, with govovernments granting certain concessions, zoning exceptions, infrastructure assistance, etc. So I suppose the grants you talk about apply mainly to Third World countries like ours. But even with this caveat, there are many energy and water export projects in poor countries that are totally financed from beginning to end by private capital. Conversely, such projects often do involve public-private partnerships in rich countries when the government wants a bigger slice of the revenue pie.

No one knows what the cost of oil will be next year or the year after, although at today’s prices, this project has no viability. There is a school of thought that says oil will be cheap for decades to come which means that all of the alternatives — wind, solar, geothermal, hydroelectric, and nuclear — are now dead on arrival.

Haz, absolutely brilliant.

I believe Gonsalves knew exactly what he was doing, he needed to PetroCaribe money to pay wages and towards the airport.

He has had the country once more shafted to get an airport in his name.

Mr. Samuel, I must repeat Peter’s sentiments: Absolutely Brilliant Analysis! You have correctly stated that the ULP’s handling of this matter is aggravated by the administration’s own “Negligence and Ineptitude”.

This geothermal energy “Game Changer” will join a long list of “bungled projects” once touted as innovations by the ULP. It is sorely disappointing because some of those projects had positive potential, only to suffer from poor planning, incompetent execution, and/or lack of effective management where the project actually came to fruition.

I eagerly look forward to reading Part 2.

Many thanks. This is quite educational. I will save this article for future reference …. Hope you don’t mind.

Vinci Vin

Very lengthy reading based on wrong assumptions, hence faulted recommendations. However in light of the communication strategy of the project and as a professional, I will respond in that regard. I await Part 2 regarding project schedule, so all concerns can be addressed appropriately.

We’ll hold you to this promise, Mr Dacon. And I hope you’ll do better than Dr Matthias did.

Here we go again! Deja Vu. Thanks Haz, for once again daring to reveal the nakedness of the Emperor. I await with bated breath, Mr. Dacon’s response. At this stage, I will only say to Mr. Dacon, please try to avoid red herrings and polemics, and stick to facts and science. As you wish to do, Mr. Dacon, I also will reserve further comment until you have come to the table with yours.But for God’s and Vincentian’s sake, be truthful and honest. Do not be afraid of the Emperor. Deal with the issues laid out by Haz, and tell us how, in the global scheme of things, he is wrong. In so doing, I will invite you to point to Nevis and Montserrat, as well as Dominica. That is all I will say for now.

Thanks Haz Samuel for a thorough and well researched article.

I am not surprised that Gonsalves and the MNU has no idea about how to do things like alternative energy and particularly whether they are interested in these subjects.

In early 2002 I supplied the PM’s office with a well-researched paper from Raymond James Investors (a US Wall Street firm) on what was about to happen in energy but it was ignored.

You wondered why the Gonsalves regime did not apply to the EU in the 2008 time period when grant funding was available for the initial phases of geothermal exploration. Well, recall that it was at this point that Gonsalves was fending off accusations of rape of Ms. Andrews.

So his attention was somewhere else. Not on our business. And this is why I say to so many people who tell me the rape accusation was Gonsalves “private business” that there is no such thing for leader of a Government and we must take it seriously, even if it were not criminal.

Further, you noted that the Gonsalves regime failed to apply to the OAS which also had funds available for said purpose. No way that a regime that has so many questions of corruption floating around will apply to the OAS for US funds. They had to be afraid of being found out if they got such funds and could not fully account for them later.

As a people we have paid a high price, a very high price for ignoring corruption in our midst and unfortunately that bill will take a couple generations to be satisfied.