By Phillip C. Jackson (digital economy researcher)

Email: [email protected]

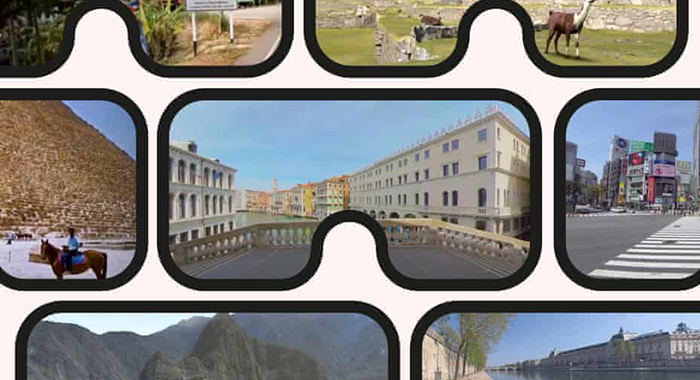

This article proposes a model for implementing virtual tourism products as a sustainable response to shocks to the tourism industry occasioned by travel restrictions in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The idea of building out Virtual Reality (VR) tourism as a product for its own sake was first presented by the author at a regional conference on science and technology for development back in 2012.

The ideas presented generated very interesting discussions by various stakeholders at the conference, but nothing was done to move us in this direction. In the current pandemic scenario, we have to treat virtual reality tourism (VRT) development as urgent and critical.

Before we get into the actual proposal here are a few definitions and explanations to orient the reader.

What is virtual reality?

Virtual reality (VR) is the use of computer technology to create a simulated environment. Unlike traditional user interfaces, VR places the user inside an experience. Instead of viewing a screen in front of them, users are immersed and able to interact with 3D worlds. By simulating as many senses as possible, such as vision, hearing, touch, even smell, the computer is transformed into a gatekeeper to this artificial world. The only limits to near-real VR experiences are the availability of content and cheap computing power.

The major players in the global VR include Oculus (owned by Facebook), Google, HTC, Samsung, Sony, and Lenovo. Due to rapid technology innovations, many of the companies are increasing their market presence by securing new contracts and tapping new markets. The leading content areas at the moment are: gaming, media and entertainment, retail, healthcare, military and defense, real estate and education.

The VR market was valued at US$17.25 billion in 2020 and is expected to reach US$184.66 billion by 2026, at an annual growth rate of 48.7% over the forecast period 2021 – 2026. By 2020 some 80 million VR headsets were sold. As competition drives affordability more and more persons will adopt VR technologies for accessing various content.

Here is a good introduction to VR on YouTube:

This current proposal is based on a number of core assumptions.

- In a post Covid-19 Pandemic world, tourism-dependent countries have to innovate to diversify their product offer anticipating uncertainty in travel.

- VR technologies provide a real opportunity for us to virtualise our beautiful landscapes and seascapes and package them for a growing market of consumers I describe as “Digital Dwellers”.

- As VR content can be accessed remotely, these products circumvent travel restrictions, and has the extra benefit of massively expanding the consumption of our products without having to worry about direct environmental degradation of land and sea environments. In other words, the carrying capacity of virtual SVG can be limitless.

- As the gadgetry for accessing virtual reality content becomes more affordable, adoption of these technologies in the population would be limited by the availability of quality and interesting content.

- Global VR technologies and content companies would be eager to partner with a variety of entities to encourage content production, including tourism-based content, in an effort to grow the VR ecosystem.

- St. Vincent and the Grenadines and other tourism-dependent small island states have excellent scenic sites and pathways on both land and in their marine environment that are perfect for virtualization and accessible through various types of VR systems.

Some critical practical and institutional considerations to build out the ecosystem for sustainable virtual tourism in St. Vincent and the Grenadines and the wider Caribbean.

- The virtual tourism concept should include the entire gamut of digital reproduction of our appropriate physical environment, from still photos in all its variations, including 360 degrees view, to videos with all its variants, to fully immersive 3D virtual reality reproductions.

- Efforts should be made to provide the platforms and mechanisms for various users to aggregate, narrate and curate these various digital assets.

- In the case where expensive specialised equipment is needed such as for the capture of high-quality, high-resolution videos for VR rendering, partnerships should be sought with leading manufacturers of such equipment.

- The same institutional arrangements should be made with global players in the storing, archiving and distribution of VR content, including those who produce the consumer side technologies like consoles and headgears. These two last suggestions are predicated on the belief that major players in the global VR ecosystem are eager to find ways to expand the range and type of content as increased variety and quantity of content can create a virtual cycle of adoption, benefiting all parties in the ecosystem. The earlier we move on this the greater would be the benefit of such arrangement.

- We must establish the intellectual property (IP) framework to first protect the digital reproduction of our landscapes and seascapes as a geographical indication (GI) or some other appropriate IP. This will guide us in negotiating the terms of partnerships with leading global entities. The legal and regulatory work may require some joint innovation and as such a regulatory sand-boxing approach may be useful here.

- The communities where appropriate sites for potential virtualisation exist should be engaged within a larger community tourism approach. This is to ensure that appropriate benefits of these innovations accrue to the local communities and create a sense of ownership. From a sustainability perspective it is expected that VR experiences will drive interest in actual visits to these sites when travelling becomes possible. In this regard, the community should be ready to host actual visitors at well-maintained sites.

- To get us started I suggest that the mechanisms be put in place to select a number of scenic sites and routes, both terrestrial and marine, on all our islands and conduct a survey to determine the most popular ones that may be virtualised. This can be complimented by a review of online feedback for persons who have previously visited. Some top candidates immediately come to mind. This list is mainly suggestive and does not reflect any particular preference of the writer.

- The Botanical Gardens

- La Soufriere hike, including the crater

- Cycling the east coast of St. Vincent

- Dark View Falls and river hike

- Hiking Ma Peggy in Bequia

- Rowing the nearshore of Villa and Indian Bay Beaches as well as the Buccament Bay area

- Diving in the Tobago Cays and other pristine dive sites

- Developing and virtualising an “indigenous village” informed by our historical and archaeological knowledge

The COVID-19 Pandemic has severely affected global travel. This has adversely impacted the income of tourism-dependent countries like ours. Virtual reality tourism (VTR) is a viable option to create revenue for these countries, as the emerging technology and consumer trends make VRT products possible and affordable. We need to move early to create productive partnerships with global VR technology and content companies. These partnerships will require legal innovations to ensure that we benefit adequately from such partnerships. Developing an active community tourism ethos among our people will ensure the sustainability of these initiatives.

I invite your ideas and feedback on possible routes forward.

The opinions presented in this content belong to the author and may not necessarily reflect the perspectives or editorial stance of iWitness News. Opinion pieces can be submitted to [email protected].