By Rafique Bailey, Ph.D., Entomology

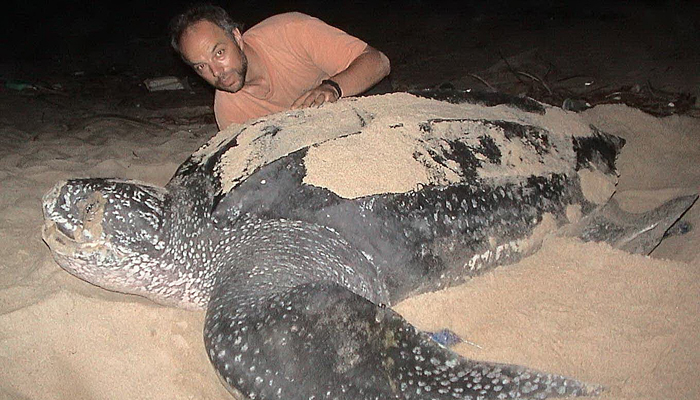

Yes, it’s true. Sea turtles are being slaughtered at alarming rates in St. Vincent, specifically on the Windward or Atlantic Coast. While there is a close season for turtle hunting in St. Vincent, the slaughtering of sea turtles on the beach at Georgetown, Byrea and Big Sand in Sandy Bay continues to take place. During the months of April to June 2013, I have found eight massive shells (carapace) from these ancient leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea) on the beach. Figures 1 to 4 illustrates some of the shells and the plastron of slain leatherback turtles in Georgetown.

From the size of the shells that were found, I estimate that the turtles must have weighed between 500 to 1,000 pounds. Dermochelys coriacea is listed as critically endangered on the IUCN red list, meaning that they have lost greater than or equal to 80 per cent of their population. The populations in the Pacific Ocean, the species’ stronghold until recently, have declined drastically in the last decade, with current annual nesting female mortalities estimated at around 30 per cent (Sarti et. al. 1996, Spotila et al. 2000). For the Atlantic Ocean, the available information demonstrates that the largest population is in the French Guyana, but the trends there are unclear (IUCN, 2000).

In my opinion, while there are laws in St. Vincent to protect sea turtles, there is little or no monitoring of the beaches by the law enforcement authorities or conservation officers of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. There are no NGOs dedicated to prevent poachers from killing these creatures when they come to lay their eggs on the beaches. In fact, there is a need for more public education and awareness in St. Vincent about why it is important to protect these endangered species. There is also the need for the formation and involvement of community groups who live near to the beaches where the turtles come to nest to help in their conservation.

In the Caribbean, sea turtle populations appears to be rebounding thanks to conservation efforts in Trinidad and Tobago, Barbados, St. Kitts & Nevis, Antigua & Barbuda, Bonaire and St. Eustatius. In Trinidad, sea turtle numbers have rebounded in recent years thanks to the efforts of the NGO’s Nature Seekers, Turtle Village Thrust, Save Our Sea Turtles (SOS) of Tobago. According to McFadden (2013), Giant leatherback turtles are now commonly sighted on Trinidad’s eastern beaches of Grand Riviere and Matura — some weighing half as much as a small car. They drag themselves out of the ocean and up the sloping shore on the northeastern coast of Trinidad while villagers await wearing dimmed headlamps in the dark. Their black shells glistening in the dark, the turtles inch along the moonlit beach, using their powerful front flippers to move their bulky frames onto the sand. In the past, this was not possible as poachers from the neighbouring towns of Grand Riviere would ransack the turtles’ buried eggs and hack the critically threatened reptiles to death to sell their meat in the market. The turtles are now part of a thriving tourist trade, with people so devoted to them that they shoo birds away from the small turtles as they first start out as tiny hatchlings scurrying to sea. The number of leatherbacks on this tropical beach has rebounded in spectacular fashion, with some 500 females nesting each night during the peak season, between May and June, along the 800-metre-long beach. Researchers now consider the beach at Grand Riviere, alongside a river that flows into the Atlantic, the most densely nested site for leatherbacks in the world.

Flourishing turtle tourism is providing good livelihoods for people in formerly dead-end farming towns, with the Trinidad-based group Turtle Village Trust saying it brings in some $8.2 million annually. The inflow of visitors, both domestic and foreign, to Trinidad’s northeast coast jumped from 6,500 in 2000 to over 60,000 in 2012. Officials with the U.S.-based Sea Turtle Conservancy say Trinidad is now likely the world’s leading tourist destination for people to see leatherbacks. In a 2009 global study on the economics of marine turtle tourism, researchers from the environmental group World Wildlife Fund found turtle tourism earned nearly three times as much money as the sale of turtle meat, leather and eggs (McFadden, 2013).

When local conservation efforts started in Grand Riviere in the early 1990s, the locals said that a maximum of 30 turtles emerged from the surf overnight during the peak of the six-month nesting season. Now, at Grande Riviere and in the eastern community of Matura, where another major leatherback colony has grown, locals say more than 700 of the turtles appear overnight at the very height of the season, in May and June.

Turtle conservation hasn’t come easy. According to a founder member of the Grande Riviere Nature Tour Guide Association, when he started out as a 23-year-old volunteer, his group used to physically drag people off the beach; that approach wasn’t really helpful and people were becoming aggressive and calling them “turtle police”. Today, the villagers feel proud that people come from all over the world to see the turtles (McFadden, 2013).

The Barbados Sea Turtle Project (BSTP) based at the University of the West Indies has been involved in the conservation of the marine sea turtles that forage and nest around Barbados through research, education and public outreach as well as monitoring nestling females, juveniles and hatchlings. Barbados is home to the second-largest hawksbill turtle nesting population in the Wider Caribbean, with up to 500 females nesting per year. Turtle nesting occurs on most of the beaches around the island, many of which are heavily developed with tourism infrastructure. This presents both challenges and opportunities for sea turtle conservation. Sea turtles are now not only an important component of the biodiversity of Barbados, but have become an integral part of the attraction of a holiday in Barbados. A visitor to Barbados has a high likelihood of seeing at least one nesting hawksbill turtle during any two-week stay at any one of the hotels on the west and south coasts in the nesting season months of May-October. A scuba diving visitor can be assured of seeing at least one hawksbill on the offshore bank reef during any one-hour dive year-round, and a visitor on a catamaran cruise will likely see several green turtles at the “Swim with the Turtles” sites (BSTP, 2010).

The BSTP operates a 24-hour “Sea Turtle Hotline” to monitor sea turtles sightings and address sea turtles emergencies. Hotel staff, visitors and beach users are encouraged to call when they see a turtle nesting or hatching, a nest threatened by high tides, or hatchlings disoriented by lights. It monitors the national index nesting beach nightly for four months during the nesting season (June-September), operates mobile patrol groups that survey 15 other nesting beaches, and monitors juvenile hawksbills on the island’s west coast bank reef. They have also produced guidelines and developed printed materials to inform visitors on how to minimize any potential negative impacts of their visits on the turtles at the “Swim with the Turtles” sites. The BSTP has assisted in productions of sea turtle documentaries for the Caribbean Broadcasting Corporation, Canadian Broadcasting Company, BBC, the Discovery Channel, and various Internet TV sites (e.g. Travelguru Internet TV) (BSTP, 2010).

In St. Kitts, The St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network (SKSTMN) is a community-based organization founded in 2003 to monitor nesting sea turtle populations and acts as an advocate for the strengthening of sea turtle protection laws in St. Kitts. St. Kitts serves as nesting ground for three species of sea turtles, the Leatherback, Hawksbill and Green Turtle. The objectives of this organization is to develop a longstanding sea turtle conservation programme, to provide community awareness about the plight of sea turtles and as an alternative to sea turtle harvest, provide non-consumable sources of income to communities.

Through a grant from the UNDP Global Environmental Facility small grants programmes, fishermen and local citizens were recruited and hired as full time technicians to collect scientific data regarding sea turtle management and health and to lead eco-tours. Technicians received training in data procurement, tagging and management procedures and tour implementation and enactment. An eco-tour programme in which visitors accompanied by trained guides to observe nesting female Leatherbacks was develop in 2009. Income generated goes directly back into the project to cover salaries and outreach cost.

Other components of the programme include the removal of marine debris from nesting beaches, recycling of glass bottles into jewellery, there is also a public outreach programme focusing on visitors and local villagers, a two-week sea turtle camp for children is hosted annually, and the training of hotel staff to implement sea turtle programmes for their guests. Because of these activities, the St. Kitts Sea Turtle Monitoring Network (SKSTMN) was awarded the most eco-friendly business award by the St. Kitts Tourism Authority in 2009.

Conclusions and Recommendations for St. Vincent

Based on the success stories in other Caribbean countries, it is reasonable to believe that sea turtle conservation has the potential to be a viable industry in St. Vincent. The beaches on the Windward coast of St. Vincent (Georgetown, Byrea and Big Sand in Sandy Bay) serves as nesting grounds for Leatherback and Hawksbill turtles while beaches on the Grenadines such as Park Bay in Bequia and Bloody Bay in Union may be used by Hawksbill, Green Turtles as well as Leatherbacks. These nesting grounds are currently under threat from natural elements such as erosion, human induced environmental pressures such as habitat destruction and modification, illegal sand mining, egg and meat poaching, marine debris (plastic bags and bottles, pesticide containers, discarded electronic appliances, dead animals). There is also an open fishing season for sea turtles in St. Vincent where sea turtles are caught by fishermen, some of them using gill nets instead of trolling with hook and line. Additionally, there is also a lack of public education and awareness in St. Vincent about the importance of protecting and preserving these endangered species for future generations. I therefore recommend that the relevant authorities consider the implementation of some eco-tourism projects on St. Vincent and the Grenadines with turtle watching as an integral part. However, for this industry to reach its full potential, infrastructure for research, public outreach, tours, vendors, handicrafts and recycled jewellery project must be developed adjacent to the main nesting beaches. The continued development of these projects and partnerships will ensure a brighter future for sea turtles and the communities that host them.