By *Jomo Sanga Thomas

(Plain Talk, April 28, 2019)

When Camillo Gonsalves delivered his maiden address to Parliament in 2013, political watchers declared it one of the best opening statements any politician had made thus far to the local assembly. Before that, many who heard him during the campaign for Constitutional reform had been so impressed with the depth and breath of his presentations that they openly commented that a new political star was on the horizon. By the campaign for the 2015 elections, even more persons, myself included, declared that Camillo had surpassed his father as a stump speaker.

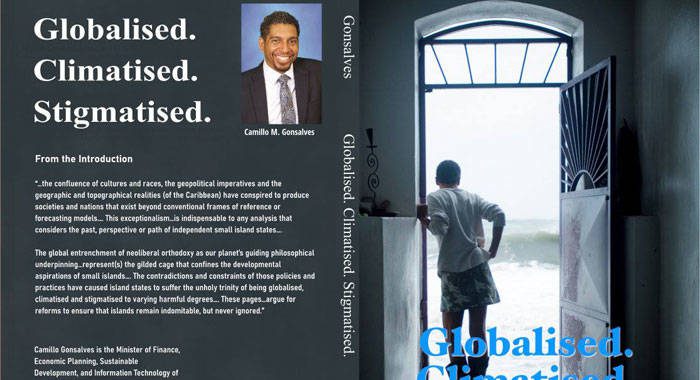

And now this. “Globalised, Climatised, Stigmatised”, a thin volume that is chock full with information that debunks old myths, grapples with new ideas and locates small-island states in a global context. This first text by our finance minister may be just the beginning of a series of thought-provoking publications on matters large and small, simple and complex, local, regional and international.

Compartmentalized into three sections, the first, “Globilised” looks at the stranglehold of debt aid and trade, the efforts of small island states to carve out a niche, the problem of inequality and poverty that continues to plague most small-island economies. Gonsalves also looks at the role of government as a catalyst for change, economic stability and development.

Section two, “Climatised”, looks at the existential threat which global warming presents to planet earth, but more particularly, vulnerable societies, which are constantly assaulted by droughts, erosion, storms, floods and hurricanes. Gonsalves says problems are magnified when governments do not have the economic resources to fund revival and survival, much more focus on development and the satisfaction of the needs of citizens.

Section three, “Stigmatised” looks at the many ways in which the international financial and economic architecture is stacked up against small-island states and the efforts of some states, including our own, to “punch” above our size and resources with tangible results.

The book concludes with Gonsalves being the Keynesian pragmatist in arguing for an alternative out of the current morass in which most small-island states find themselves.

The book is as readable as it is digestible. It is not heavy on jargon or statistics; neither is it beyond the intellectual reach of the ordinary man. As is the style with most authors these days, Gonsalves prefaces each chapter with one or two quotes.

The books opens with the Jamaican saying that now has regional reach “me small, but me tallawah”. In the introduction he makes the understandable but troubling claim for Caribbean exceptionalism, citing as proof the facts that these dots on the seascape have already produced three Nobel Laureates, Usain Bolt and Gary Sobers. Exceptionalism is akin to the claim by some that a person or family comes from “good stock”. We only have to go back 80 years to see that all came from the same stock. Connections and social position impact on life chances. Camillo Gonsalves is exhibit A.

Gonsalves traced the new economic regime back to Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, a time when most small islands were regaining their independence after long years of colonial domination. He correctly noted that by Independence the neo-liberal agenda was in full flight and the rulers of the world “imposed an ideological homogeneity through the force of law, might and money”. This is even more so today than ever before.

Bill Clinton once said that globalisation is the natural order of things. Gonsalves argues in part, that this is not completely true and notes that institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund have presented schemes for the guidance of countries that they themselves admitted were wrong headed. He offered the example where the IMF, as early as 2012, admitted to being wrong on austerity. He praised the Keynesian economists who have long maintained that periods of economic downturns are the times when monies should be pumped into the economy. Implicit in his argument, is that his father was right in engaging in counter-cyclical financing before and particularly after the world economic downturn in 2008.

Gonsalves’ book argues that debt, in and of itself, is not bad. It is what is done with the borrowed money that is crucial. He offered proof that a large chunk of borrowed monies are intended for disaster recovery and climate adaptation. He makes the case that debt must be viewed differently from the days of yore, and places a call for developmental investment, debt relief and restructuring if small islands are to survive.

Some writers have described aid as raid, and have used persuasive statistics to demonstrate that the “donor” countries get far more than they give from the countries they offer assistance. Gonsalves looks at aid and trade, the Banana Wars that led to the “Green Gold’ demise in our region, the WTO and different trading arrangements.

Gonsalves says that some have argued that these institutions and agreements are reasonable and in the interest of all. He is, however, not of that mind. He points to the effort of some countries to fight back. They win a battle and are ignored but generally the arrangements benefit the rich and powerful. Gonsalves seems optimistic that niche development is possible if not immediate. He will have to develop and clarify his arguments on niche development even more, because it is apparent that unless there is a total realignment in the international economic, financial and trading architecture, small islands would remain hewers of wood and carriers of water.

As early as 1984, Fidel Castro told a conference of economists that the debt was immoral and unpayable and should be scrapped. Today countries are mired in even more debt and the inequality gap has widened. Gonsalves cites the emergence of the new gilded age of the super-rich and praises Keynes’ insight that “greater equality complements greater economic performance”. He is right, but how do we get there from here? Gonsalves offers pragmatism. Blinkered by the dominant prevailing view, he disregards the efforts of the people in Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, France, Spain, Croatia, South Africa where people actively challenge the neo-liberal capitalist status quo and mistakenly conclude that “there is little popular appetite” for real change.

The author sells the argument that the private sector is not the be all and end all of development. He proffers that there is ample room for state intervention as a spur to local development. On matters of climate, Gonsalves notes that the threat is real, talk is glib and solutions are out of sight. Ominously, he says “destruction is all but certain” if we continue on this path.

The writer chronicles the ways in which the rich and powerful changes the rules to meet their purposes. The best examples being the tax regime aimed at regulating offshore financial services. We grew up hearing of secured secret Swiss bank accounts, today we are blacklisted and penalised for “exploiting a niche”.

Gonsalves triumphantly proclaims that the small islands punch above their weight. As proof, he discusses what he calls influence as a commodity, and influence as security, to show that small states can stay the hand of the rich and powerful. The argument is useful but overdrawn. This remains a world where might continues to make right.

The weakest part of the book is the conclusion. While claiming “islands must reject and reinvent the circumstances of their neglect and subjugation”, Gonsalves seems to suggest that the prevailing order is so dominant that little or nothing can be done to bring real relief and development.

A better way is indeed possible. As Hilary Beckles argues “few enslaved Africans in 1830 would have imagined that emancipation was around the corner, but it came”. Pessimism and the acceptance of the prevailing order is not a good basis for transformative leadership.

Although Globalised. Climatised. Stigmatised breaks no new ground it is a good read and provides much food for thought.

*Jomo Sanga Thomas is a lawyer, journalist, social commentator and Speaker of the House of Assembly in St. Vincent and the Grenadines.

The opinions presented in this content belong to the author and may not necessarily reflect the perspectives or editorial stance of iWitness News. Opinion pieces can be submitted to [email protected].

A sycophantic review by one Comrade of another Comrade’s self-published work is like one hand clapping.

Jomo I understand that you are in a Rock and a hard place. You have to sing praises to the master in order to be in the good books of the very people who control the Ulp. The average VincentIan knows that you are not well admired in the Ulp caucus .

Jomo there is a common adage that goes like this, you are better judged in the manner in which the you treat the most vulnerable in society. Camillo’so alleged treatment of Youggie Farrell is diplorable. […] Jomo have to sing all praises to Camillo is understandable from the point of view that election is imminent. The good African is portraying an inferiority complex of enormous magnitude.

Poor Jomo who is trying desperately hard to keep company with the ruling elite. He would have been more relevant if he maintains a voice of reason. But by being in the same bed with Camillo who alleged to have exploited a vulnerable woman, gives us an insite in the person who he really is. No better the beef no better the barrel. The apple is said not to fall from from the tree.

It is already an exercise in vanity to publish your own book. I get a sickening feeling when someone rushes out to praise a person who exercises thier vanity. When that person is from the same company or political party it is even more sickening. Arrogance, Narcissism and all its adherents are dangerous when found in high political positions.

Jomo Thomas is too enslaved by his out-dated notions of slavery and “blackness”. He should break the bonds of his enslaved mind. Cast-off the bonds of his feelings of self-pity and inferiority. He wants all Vincentians to be enslaved as he is. He should instead take stock of what he has, what we have, and use it to the best of his/our ability. His mindset will otherwise keep us down by enforcing the thought that others owe us something for history or what thier ancestors may have done.

Jomo is blind to the history of other nations and other peoples. Virtually all nations and all peoples had thier hard times and most of them do not dwell on a notion that they are due a financial handout and that everyone should feel sorry for them. How many MILLIONS of Russians died during and after WW2. Should Germany pay? Should the descendants of Stalin pay? What about all the mass murders in Asia, South America in recent history or the mass murder going on in Yemen or Africa today? I wonder if they will beg for handouts and demand that everyone feels sorry for them before they send a big check to the comrade? Jomo needs to wake-up because I doubt that he is going to get any political traction for his reparations attitude. Most all healthy-thinking Vincentians exist in the here and now and want a way forward. Those that sit around and cry about how unfair the world is are wasting thier time and energy. Jomo wants to keep them there, enslaved! He is one of the privileged in SVG and somehow, those that notice his constant cry-baby political strategy see it as a losing environment for our society that will get us nowhere.

Why doesn’t Jomo instead use his brain? At least Camillo does some of the time, but not enough to be a leader. Ivan O’Neal also cries about rich white foreigners on Mystique but he is at least far ahead of these cry-babies. At least O’Neal attacks the real policy that is at fault for that situation. Isn’t it odd that Jomo nor Camillo never talks about that?

You hit all the nails squarely on the head with these perceptive comments.

A man trapped in the past can never move forward.