A senior lawyer who has acted as an Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court (ECSC) has made out a case against abandoning jury trial, as some of the court’s jurisdictions, including St. Vincent and the Grenadines, are proposing.

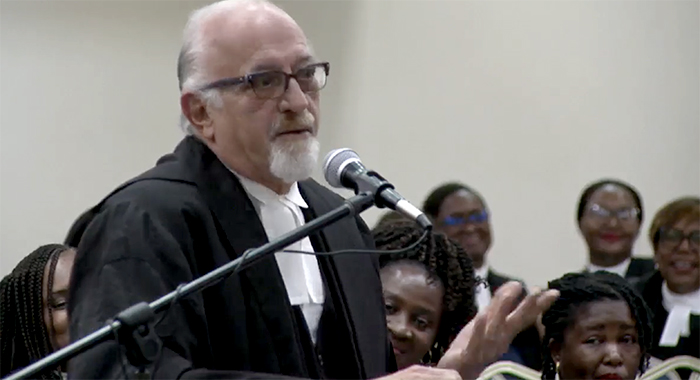

“There’s nothing more just in our system than the word of the jurors,” King’s Counsel Thomas W.R. Astaphan told a special sitting of the ECSC in Grenada on Friday to mark the beginning of the law year.

Astaphan, a Kittitian based in Anguilla, pointed out that jury trials date back to Magna Carta, which was issued in 1215 and altered in 1216, 1217 and 1225.

“Clause 39 of the Magna Carta states, ‘No freemen shall be taken or imprisoned or disseised or exiled or in any way destroyed, nor will we go upon him nor send upon him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land’,” Astaphan said, noting that “disseised” mean “dispossessed”.

“So, it is in 1215 in the agreement between the king and the uprisers, in order to settle that, that the first manifestation of the right to a jury trial was born,” Astaphan noted.

He said the right to a trial by jury is a right which evolved from the Magna Carta, and was elevated over centuries as a right of common law.

And when former colonies in the Caribbean got written constitutions, that common law right was elevated to a constitutional right, Astaphan reasoned and referred the court to a number two cases to support his view.

Prime Minister of St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Ralph Gonsalves, a lawyer who is also minister of legal affairs and national security, has listed judge-only trials amidst suggested changes to the justice system.

Director of Public Prosecution Sejilla Mc Dowall has spoken publicly in support of the suggestion, which some lawyers have expressed uncertainty about.

In December, at the closing of the assizes in Kingstown, a lawyer suggested that if the country moves to non-jury trial, there should be a panel of judges rather than a single judge

Other lawyers have suggested that the accused should be given the option of a jury or judge-only trial.

Astaphan said he did not think there was another person in the room in Grenada who was as studied in the law and who has the experience, he has had in the criminal courts of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States.

“… long and deep experience — prosecuting, defending?” the lawyer said.

He pointed to Clause 40 of the Magna Carta, describing it as “one of the exemplary points of our court from its inception to know that this doesn’t apply”.

That clause says: “To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice.”

Astaphan said the constitutional right to a trial within a reasonable time is, therefore, rooted in the Magna Carta.

He said he mentioned this clause because “there are a series of judgments coming out of the courts of the Commonwealth in respect of the delay right of justice — with the notable exception of the Canadian Supreme Court — which seem to suggest that delay right of justice as is in the Magna Carta or the constitutional right to a trial within a reasonable time in our constitutions in the OECS is a conditional right.

“That is to say, the right to be tried within a reasonable time is conditional upon something else; dependent upon whether the other rights secured by the relevant section of a fair trial is still possible, regardless of the number of years which have gone by.”

The lawyers said that the third right engaged in that section is right to a fair trial within a reasonable time before an impartial tribunal.

“Those are the three separate rights encompassed in that section,” Astaphan said.

He told the court that what has developed, as evidenced by cases out of Turks and Caicos Bahamas, England, particularly, “is that the right to be treated within a reasonable time is subsumed under the right to a fair trial.

“And even if 20 years have passed, the judges will say, ‘Well, if he could get a fair trial, now, even though we acknowledge that the right to a trial within a reasonable time has been infringed, then the trial can go on.”

Astaphan said there is a case from the Court of Appeal out of St. Lucia decision, which addresses the issue from his perspective – “time has gone, too much time has gone. It’s Ok.”

He said that when extra regional judges pass judgment on matters of this nature that binds the ECSC, “they seem to forget their own legal history…

“I’m a proud West Indian nationalist. I grew up in the era of strong trade unions, and revolution towards independence, etc. That’s my background, politically.

“So, I have nothing but respect for our institutions. And even if I think sometimes, we do wrong things, I still have faith in us, we have to go forward. … I must remind us all that the constitutional right to be tried within a reasonable time is rooted in the Magna Carta, it’s not some 1962 onwards, fashionable thing.”

Astaphan pointed out that the Privy Council had ruled that notwithstanding the fact that the law that created trial by judges o was passed because UK authorities needed Misick (the defendant) to be tried without a jury, the law did not infringe the constitution.

“But then you pause and you say, ‘Okay, the Privy Council says so, they’re an ancient institution, they’re our supreme apex court so it must be right.

“But I said earlier, I’m a rebel. I don’t think they’re right. I think they were political with that decision. And if I mash toes now m’lady you know me very well, I really don’t care.”

The lawyer argued this was not the only Privy Council decision that has “a political overtone”.

“The Chagos Island cases where the people of the Chagos Islands, the natives, were removed from the islands so that Britain could contract a lease with the US government for a naval base, that is a political decision.

“Which brings me to the most important thing I wish to say today, … the time has come now, when all of us in the West Indies need to accede to the Caribbean Court of Justice, and move away from the Privy Council.

“Let our own people, people who are of us, and we of them, who are born with us and grew up with us and experience with us our social and cultural and economic experiences, let them sit in judgment of me and of us.”

Astaphan said he hopes that some politicians were listening to begin to focus on the transition.

“… one of the things you hear, ‘Well, it can be political.’ Okay. So what? We’re human beings. Sometimes we are political, inadvertently. But the Privy Council is political which is why I raise those two cases; two political decisions. Let my own people be political with me. Not foreigners. And I mean, no disrespect…”

Astaphan also argued against denying people their day in court on civil or criminal matters on procedural points.

“I would have thought that the whole purpose of justice in a democratic society is to serve the people. It’s not to serve institutions. It’s a people’s court; it’s the people’s justice. That’s what I think I might be wrong. I may be wrong. Therefore, to deny litigants their day in court, civil or criminal, on a procedural point, is to deny them their justice,” he said.

He, however, said he was happy that the criminal procedure rules provide the judges “with unnecessary ammunition to ensure that substantive justice is faithfully served.

“The point I’m trying to address to myself, but loudly, is that litigants must not be stopped in their tracks, by breaches of the procedural rules. There is a way you can fashion a remedy to allow them to have their day in court and we must encourage that because it’s their justice.”

He said that in so far as the requisite part of the CRP applies, “it should be used by the courts in every instance to benefit the citizens right to justice”, adding that to the extent that other rules don’t they should be amended.

The jury system has been working for years. There is a saying that if the system is not broken it does not need fixing. Natural justice is better achieved by the system where jury prevail.