By Kenton X. Chance

KUMEJIMA, Japan — “You’ll love it in Okinawa,” Floyd Takeuchi, the programme coordinator, told me as, on Oct. 25, we prepared to depart chilly Tokyo with its hordes of people, skyscrapers, and bustling traffic.

“That’s Okinawa’s Mopion,” I thought, remembering Takeuchi’s words, as I flew over a sandbank that immediately brought to mind a similar geological feature, the size, or very existence of which depends on the tides at the southern end of St. Vincent and the Grenadines (SVG), the Caribbean island nation and my home.

When we landed at Kumejima (Kume Island), (about 100 kilometres west of Okinawa’s main island), the reason for Takeuchi’s comments became obvious immediately.

There was warm sunshine — a welcome contrast to Tokyo’s autumnal chill — and the vegetation looked more Caribbean. The skyline was determined by the height of trees, not the intrusion of high-rises. Where the trees ended, there was blue, rather than Tokyo’s grey.

I had come to Kumejima along with four other journalists from the Caribbean and the Pacific and along with two Japanese university seniors headed for jobs in journalism.

Our visit to Japan, organised by the Association for Promotion of International Cooperation and the Foreign Press Center Japan, focused on disaster preparedness and sustainable development. That’s according to the official programme. We discovered that we were also being introduced to the nuances of a culture that has delivered contributions to the human spirit as diverse as one of world’s most delicate cuisines to one of the tallest towers on the planet.

All this began to become clear when we arrived in Kumejima on Oct. 25, after four days on Japan’s main island, Honshu, where the capital, Tokyo, is located.

During those four days, we had visited the city of Kawasaki, south of Tokyo, to observe garbage collection and recycling processes that turned spent paper — ranging from books and magazines to drink cartons and train tickets — into high-quality, lint-free bathroom tissue.

In Kasukabe City, north of the capital, we had seen how a massive man-made underground tunnel system (The Metropolitan Area Outer Underground Discharge Channel), built at a cost of US$2.1 billion, had reduced the number of houses that were flooded due to typhoon-related torrential rains from 34,000 in 1991 to just 43 last year.

On the lighter side of things, we had ascended to the observation deck of the 634-metre-high (2,080 feet) Tokyo Skytree, the world’s largest broadcast tower and Tokyo’s tallest built structure which is an engineering monument to a soaring human spirit. Closer to the ground, we had visited the Meiji Shrine, where, among other things, we got glimpses into Japanese wedding ceremonies and Shintoism, Japan’s native religion.

As we drove from Kumejima Airport to our first stop on the 63.5-kilometre (39-square-mile) island — three and a half times the size of Bequia — I began to compare the scenery with that of Caribbean islands.

The fields of sugar cane could have been mistaken for those in Barbados. The potato fields looked much like those in St. Vincent, except that the land was flat, much more like those in agro parks in Manchester, Jamaica.

Notwithstanding its status as part of a developed nation, Kumejima faces many of the same problems that we have to confront in SVG and other small island states.

These include the threat of natural hazards such as typhoons and earthquakes, rising sea levels, degradation of the marine ecosystem as a result of climate change and the actions of humans, the threat of agricultural pests and diseases, and a shrinking population.

Kumejima has 8,000 residents and receives about 120,000 visitors annually. They want to increase this to 150,000, says Yukio Nakamura, director of the Planning Section of Kumejima Town Office.

In addition to tourism, the other major industries are sugarcane, livestock, prawns, “green caviar” — a species of bryopsidale green algae from coastal regions in the Indo-Pacific that is called “sea grapes” locally — and purple potatoes, a staple for which the island is famed, Nakamura says.

And the island has been able to assist each of its industries using its most abundant resource, one that is also plentiful in SVG: the cold water of the deep sea.

The concept has been dubbed the “Kumejima Model” and includes the use of the clean, cold, nutrient-rich deep-sea water for warm baths in spas, cosmetics production, fisheries, hydrogen production, and desalination.

It is part of the island’s goal to become 100 per cent sustainable by 2030. And while the target reflects the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, Naoki Ohta, the OTEC project promotion officer at the Kumejima Town office, jokes that the UN, which adopted the SDGs in 2015, copied them from Kumejima.

The island spent US$25 million to construct a deep-sea water intake, which came on stream in 2013.

At the Ocean Thermal Energy Conversion (OTEC) Demonstration Facility, engineer Shin Okamura, who works at the Secretariat of Kumejima’s Resource and Energy Association Institute, explains how cold water from the deep sea is mixed with the warmer surface water as it flows around a container of refrigerant, which, in turn, generates the steam that drives the turbine that produces some 110 kilowatts of electricity.

The concept of OTEC in energy conversion is not new, but Japan and Hawaii are the only two jurisdictions that have succeeded at it. Other plants are under development around the world, including in Martinique.

Japan spent US$2.2 million to install an intake 1.4 miles from shore and 2,007 feet below the surface that carries some 13,000 tonnes of water to shore every day, a volume second only to Hawaii’s.

Around the extraction of this 8- to 10-degree Celsius water, has sprung up several industries that have generated US$22 million in revenue annually over the past decade. Of those sales, 43.3 per cent comes from the island’s prawn industry.

Another 18 per cent comes from the growth of green caviar, an industry that grows specialised seaweed that’s considered a delicacy.

A further 23.8 per cent of the revenue generated from the seawater comes from Kumejima’s homegrown cosmetics manufacturing industry.

The hope is that within a few years, the island’s OTEC plant, which is now a research facility, can generate one-third of the six megawatts of electricity that Kumejima needs.

Kumejima is also exploring the use of deep-sea water to reduce geothermal temperatures by running the freezing water in pipes under farms, thereby making the soil cool enough to grow leafy vegetables during the scorching summer months.

I was amazed to learn that some companies prefer deep-sea water for their cosmetic products — because it is clean and rich in minerals.

And Atsushi Omichi, president of Point Pyuru, a cosmetics company, knows much about this.

A former beautician, Omichi says that cosmetics are 50 to 60 per cent water.

“And the people who order from us are looking for good, clean water and that’s why they are coming to us,” he said, noting that his firm currently supplies products to 80 cosmetic companies and uses 10 tonnes of deep sea water daily to do so. The deep-sea water is so prized that other firms remove the salt content and sell it as nutrient rich drinking water — for a premium price.

After processing, Point Pyuru’s 10,000 tonnes of water produce 10,000 bottles of cosmetics for the high-end market in Japan and South Korea, and other parts of Asia.

But as amazing as this use of science was to me, I was more interested in how Kumejima used low-level radiation to sterilise male potato weevils, thereby wiping out the pest across the island.

This technology, which is widely used around the world, could likely be helpful to SVG and other Caribbean nations in tackling agricultural pests such as the mango sea weevil and the West Indian fruit fly.

On Kumejima, sterile male potato weevils were released by helicopter across the island. As the number of sterile male beetles rose, reproduction fell, until the pest was eliminated.

With the eradication of the beetle, potato production in Kumejima has risen to the point that it is now on course to unseat sugar — which generates US$8.8 million a year — as the island’s number one agricultural product.

Another successful project that could be of benefit to SVG and island nations around the world is the work of researcher Ryota Nakamura at OTEC.

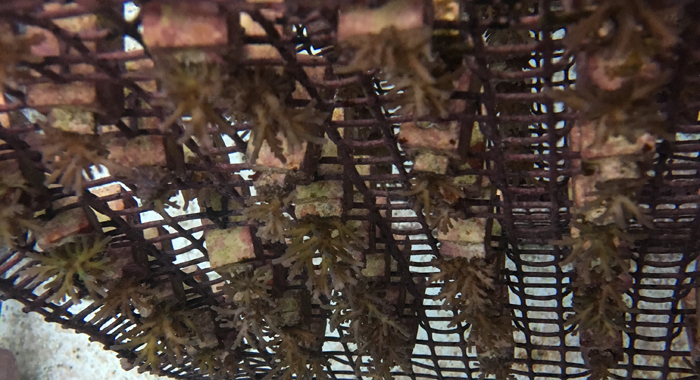

He and his team are culturing corals in surface-level seawater and growing them in a controlled environment at OTEC. They aim to transplant them to the areas in the island’s waters, where corals have been damaged by the soil washed into the sea during heavy downpours.

I have heard about how slowly coral grows. However, this never came home more powerfully to me than when I got the opportunity to view how tiny a six-month-old piece of coral is. At first glance, the delicate “baby” corals look like a small clump of sand.

Even at four years old, the corals were hardly the size of my hand.

This observation further illustrated the need to protect our fragile coral and, by extension, the marine ecosystems they sustain that are so vital to fisheries.

But my time in Kumejima was not all spent learning about science and conservation.

The night we spent on island, we had dinner with some town officials at a traditional Japanese-style restaurant.

I was beginning to wonder how much longer the social event would last, as I was still battling the effects of jet lag from my SVG-Tokyo trip, added to the hectic schedule in Tokyo, and the three hours of flying, in addition to ground travel, that brought me to Kumejima that day.

It was then that a young woman took to the microphone, saying that their special guests were to be treated to some live music — as if the banner with the flag of each country represented in our group was not enough.

Among the selections was a song that made me feel right at home, although I could only understand a few words of the lyrics. But, once one hears the chords and words of Bob Marley’s “No Woman No Cry” – whether sung in English or Okinawan dialect, as it was that night, no translation is needed.

When the musicians took an interlude and the woman who played the African drums returned to our table, I commended her on the beautiful renditions.

She modestly expressed appreciation and played down their skills by telling me that the musicians, before that night, had never played together.

In fact, most of them were from different bands, and she, herself, had only learnt about five hours earlier that there was to be a performance.

Before the night was out, accompanied by the band, I would sing Marley’s “Redemption Song” and my colleagues would represent their own countries, in song and dance.

Kumejima was the only place during my 10-day trip to Japan where the pace, geography, and weather, allowed me to go jogging — something that I had hardly had time to do given my hectic travel schedule over the previous two months.

During my workout, I felt more like I was sightseeing. While it was close to 7 a.m., the moon was still trying to hold on to the lingering remnants of the night, while the sun began to rise triumphantly over the horizon.

“The sun rises pretty late in the ‘Land of the Rising Sun’,” I thought.

As usual, I listened to a BBC news podcast during my jog. That day, it reported on the pending election in Brazil and the arrest of a man in the United States who was accused of mailing pipe bombs to prominent Democrats.

I thought about the rise of the far right recently, and how similar the beginning of this century and the last were to each other. I thought about the policies of the United States and Japan in the conflict that marred the first half of the 20th Century and how ironic that I was thinking about those things while jogging in Okinawa.

And for once, I hoped that history would not repeat itself and that a century was not so brief a time that the world would forget.

Before leaving Okinawa that day, we would visit a large reservoir where rainwater is collected and pumped, using solar energy, to farms on the island.

Before making our way to the airport for our mid-morning flight to chilly Sendai on the east of Japan’s main island, we also visited the solar farm that powered the pump.

I wished I would spend another day enjoying the peace and quiet of Kumejima. But, Sendai and the lessons of the devastating March 11, 2011 earthquake and tsunami were ahead.

And, as our departure flight — a turboprop aircraft — soared and land gave way to blue sea, I leaned my head against the cabin wall, planning to catch some sleep during the 30-minute flight back to Okinawa’s capital, Naha, before getting on a wide-body aircraft to Sendai.

“Floyd was right,” I thought as I closed my eyes.

“I did love it in Okinawa.”

Thanks for taking me on this exceptional journey by your written rendition of your experience.

Wow! It always brings me much excitement to have read of these opportunities gain especially of my people, our younger men and women in the hope that others in reading this article of the phenomena of Okinawa, of “engineering monument to a soaring human spirit”. Would be stirred to an understanding as to where we are at as a nation, given the room for development as a forward thinking people of a similar nation.

A country according to Kenton’s discoveries, yet “faces many of the same problems that we have to confront in SVG and other small island states”. “These include the threat of natural hazards such as typhoons and earthquakes, rising sea levels, degradation of the marine ecosystem as a result of climate change and the actions of humans, the threat of agricultural pests and diseases, and a shrinking population”.

I am inspired Kenton, thanks again for sharing.

FACES PLACES AND THINGS

Spectacular and breathtaking and enlightening.

Most of all, an informative account, complemented by a picturesque view of the different ‘…Faces, Places and Things,’ including ‘…the effective use of science and technology; …food production; …preparing and coping with changes in climatic conditions and cultural life of the Japanese people.’

Most wonderful!

Beautifully and elegantly written: your best essay so far, as I see it.

What struck me the most is the creativity of the Japanese people, surely their greatest resource in a country with few natural ones.

What struck me particularly is the way obvious and abundant natural resources are harnessed, such as sea water, reminding me that we are viewing the growing presence of sargassum seaweed as a nuisance as opposed to a blessing, a natural substance freely coming ashore from far away — literally a gift from God — that can easily be converted into fertilizer and other products for sale or distribution to our farmers and others.

As the old people used to say, “we are not ready.” If we were not ready then, and not ready now, when will we ever be ready?