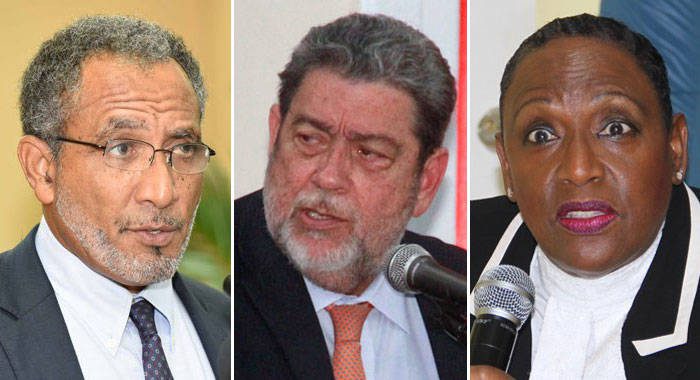

Two opposition lawmakers locked horns with Prime Minister Ralph Gonsalves, on Thursday, over the meaning of part of a law his government had passed replacing a decades-old amended legislation governing how state monies can be spent.

Opposition Leader Godwin Friday first raised the issue relating to the Finance Administration Act.

The legislation governs the timeframe within which the government must come to Parliament for approval of the use of special warrants.

A special warrant is an instrument used by the government to meet unforeseen expenses that had not been budgeted for.

The original law, dating back to the 1960s, had said that the government must bring a special warrant to Parliament for approval within 14 days.

However, the former New Democratic Party administration changed the law to give the government six months in which to do so.

When Gonsalves’ Unity Labour Party came to office, it repealed the law altogether and replaced it with the Finance Administration Act.

The relevant section of the new law says: “The minister shall no less than six months after the date a special warrant was issued cause it to be laid before the House of Assembly or cause to be laid before the House of Assembly a supplementary estimate showing the sum spent.”

And Friday, a lawyer, questioned the meaning of that section of the legislation.

“What does this mean? Do you have an indefinite timeframe in which to bring the supplementary estimates to the house? If that is the case, that can’t be what is contemplated in the Constitution.”

The government had not brought supplementary estimates to Parliament for approval of special warrants since 2014.

And, during Thursday’s debate ahead of approval of those special warrants, it was revealed that in two of the years since 2014, the government broke the law by spending in excess of EC$25 million via special warrants during one year.

Friday said the new act is not in line with the original legislation or the amendment passed by the NDP administration.

He said the law passed by the Gonsalves government seems to suggest that it is up to the minister of finance to decide when to bring special warrants to Parliament.

“If that is the contemplation, then I think that that is inconsistent with what the Constitution requires and, certainly, inconsistent with accountability,” the opposition leader told lawmakers.

“If it is an error and says it has to come within six months, then that will bring it in line with the previous act. If it is not and this is what is intended, the question is, for what purpose? Why is it changed? Is the minister saying that it is within his discretion or his good nature to say he should bring it before five years from now on but that he is not legally required?

“I don’t think that is what is contemplated in the constitution and what is contemplated by the previous legislation and ought not to be what we have here,” the opposition lawmaker told Parliament.

In his contribution to the debate, Gonsalves, who is also a lawyer, noted that the law says “when in a financial year”.

He added: “So when the not less than six months after the date a special warrant was issued, caused to be laid before the House, I take it that you should lay it within the whole context of the structure of the statute, within the 12 month period. And if we want to make it clear, we should say that. But the point of it is that any reasonably interpretation of this section, it must be within a year.”

He said that if the special warrant has to be brought to account by bringing it to Parliament within six months, the warrant may be issued but the processes for its expenditure might not be completed.

“So it is reasonable that if it is done within that year you bring it within before the end of that year and something which is wise to do is that when you bring your estimates for the year, that you should have on the order paper the supplementary estimates also.”

The prime minister noted that the opposition leader had said that the government must follow the law and adopt practices in keeping with accountability

“Well, we are following the law and I outlining how, internally, the processes of a special warrant take place and all the checks which happen…” he told law makers.

And, in her contribution to the debate, opposition senator, Kay Bacchus-Baptiste said what is required is that the law be followed.

“But how can you follow the law? The prime minister bragged that he amended the Finance Administration Act because it was so bad when he took over, so he amended it. But how was section 4 amended?” she said.

Bacchus-Baptiste the original law — the Finance and Audit Act of 1964 — says at Section 5(2): “The Prime Minister shall submit supplementary estimates for the approval of the House of Assembly as soon as possible after the issue of a special warrant and shall at the next sitting of the House of Assembly occurring after the expiration of 14 days from the date of any special warrant authorising the issue of such sum introduce into the House of Assembly an appropriation bill.”

The senator commented:

“So, here, from 1966, you had to do it as soon as possible and within 14 days. You changed the law, you say you are so interested in finance administration that you changed the law and you put a vague provision like section 28(40…”

Gonsalves, however, asked the senator to give way and said that the opposition leader had conceded that there was an amendment to the law under the NDP.

He added:

“And the point that I also want to make, is this: We did not amend the law; we repealed it in its entirety and brought in a new law which is far better. But that is not the point I am really — I am talking about she saying that it was 14 days and that we amended it to this vague thing. It was amended to 12 months.”

But Bacchus-Baptiste retorted:

“How does that change what I am saying? I said the original law. It was said clearly that it was amended to 12 months. But you changed it, repealed that amendment and brought in a law that read like this: ‘The minister shall not less than six months after the date of a special warrant was issued cause to be laid before the House of Assembly supplementary estimates showing the sum spent.”

The senator asked the prime minister if he was saying that there was a mistake in the law that his government passed.

“Is it that it should have read not more than six months? It does not appear that that is what it is supposed to be because the prime minister never averted to that fact when he was speaking — oh it was a mistake. So the clear intention was to give any time after six months within which to bring this law.”

Bacchus-Baptiste, however, said that on an interpretation of the Constitution, it contemplates that the special warrant would be brought within a year.

“… and even on reading this particular act, you can say that it may refer to because the section begins with ‘when in a financial year’, but the actual subsection that deals with the law says, ‘not less than six months’, which means that you can’t bring it before six months, but there is no limit as was in the previous one by the NDP, which said 12 months…”

The senator said that Parliament will soon be debating an amendment to the Finance Administration Act and suggested that the section be reviewed to remove any doubts.

“It cannot be acceptable to spend government money and wait five years after you have been prodded by the opposition to bring these bills before the house and then bring them all together,” she said.

Parliament went on to approve the EC$123 million in special warrant spending between 2014 and 2018.

The cheating bathbun

LOCK THEM UP, LOCK THEM UP, LOCK THEM UP, before it’s too late!

If the Law does not allow us to lock them up, if and when you do get into power, change the law to enable such future reneges to be locked up for such a flagrant breach and contempt of the Law!

You see the thing is,,Vincentians allows Gonsalves to play with them with words, in doing so, he gets to manipulate them along with the system.

I suspect the new law is in fact an attempt to circumvent the possibility of bringing a charge against Ralph Gonsalves of Misconduct in Public Office, no more and no less than that. The wording is highly suspect of being a fenagled mangle to deceive the NDP law makers.

There has got be something highly illegal about these payments otherwise they would have been declared a long time ago. Is this some of the continuation work of Maurice Bishop? Was this an attempt to not keep two sets of books but to keep one set and simply discard the rest.

The NDP should demand an enquiry, after all this was an extremely serious breach of the constitution. Its like robbing a bank and admitting doing it four years later, expecting no consequence for committing the original crime.

Misconduct in public office is an offence at common law triable only on indictment. It carries a maximum sentence of life imprisonment. It is an offence confined to those who are public office holders and is committed when the office holder acts (or fails to act) in a way that constitutes a breach of the duties of that office, most often under purposeful breach of the constitution.

The offence should be strictly confined. It can raise complex and sometimes sensitive issues. The Director of Public Prosecutions [DPP] should be asked to resolve any uncertainty as to whether it would be appropriate to bring a prosecution for such an offence. In the failing by the DPP, there are other regional and international bodies that can be sort for advice on appropriate action and how to go about such an action.

Where there is clear evidence of one or more statutory offences, they should usually form the basis of the case, with the ‘public office’ element being put forward as an aggravating factor for sentencing purposes.

The decision of the Court of Appeal in Attorney General’s Reference No 3 of 2003 [2004] EWCA Crim 868 does not go so far as to prohibit the use of misconduct in public office where there is a statutory offence available. There is, however, earlier authority for preferring the use of statutory offences over common law ones. In R v Hall (1891) 1 QB 747 the court held that where a statute creates (or recreates) a duty and prescribes a particular penalty for a wilful neglect of that duty ‘the remedy by indictment is excluded’.

In R v Rimmington, R v Goldstein [2005] UKHL63 at paragraph 30 the House of Lords confirmed this approach, saying:

“…good practice and respect for the primacy of statute…require that conduct falling within the terms of a specific statutory provision should be prosecuted under that provision unless there is good reason for doing otherwise.”

The use of the common law offence should therefore be limited to the following situations:

Where there is no relevant statutory offence, but the behaviour or the circumstances are such that they should nevertheless be treated as criminal;

There is absolute oodles of case law and procedures in and throughout the Commonwealth. Perhaps even advice from the Commonwealth legal department should be initially requested.

Going into parliament and trying to make good an ancient breach retrospectively is simply not good enough because the breach in this case was long out of date for rectification.

It, was not until the NDP complained, that any action was taken in trying to rectify this matter. But what would have happened if the NDP had not brought it to the attention of Parliament? Would it all have been lost in time? Or continued to be hidden from view?